Why 'Good Vibes Only' Culture is Killing Critical Thinking

The dangerous rise of toxic positivity and societal self-deception

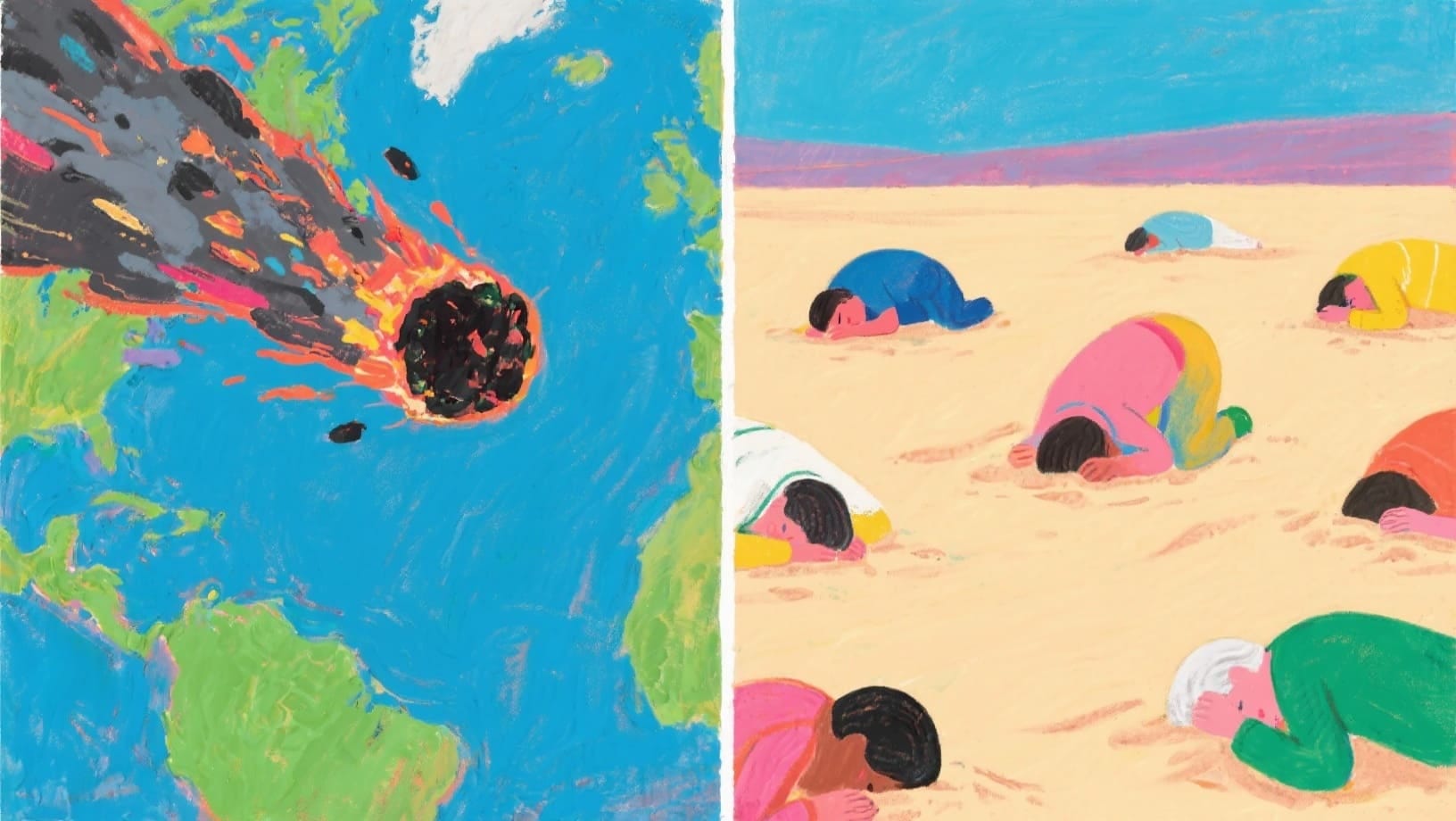

Remember the film “Don’t Look Up” from 2021, where a group of scientists tries to draw the attention of the government, president, and society to the obvious threat of a meteorite heading straight toward Earth, which would most likely destroy humanity if no action is taken?

This film is deeply ironic, isn’t it? But it contains a lot about our human automatic ability to close our eyes to problems and pretend everything is fine.

The Epidemic of “Positive Thinking”

In the relatively stable years following the end of the Cold War, Western societies, and later like a pendulum other countries with medium+ levels of security, naturally calmed down because it seemed that all global troubles and the threat of nuclear wars were behind us.

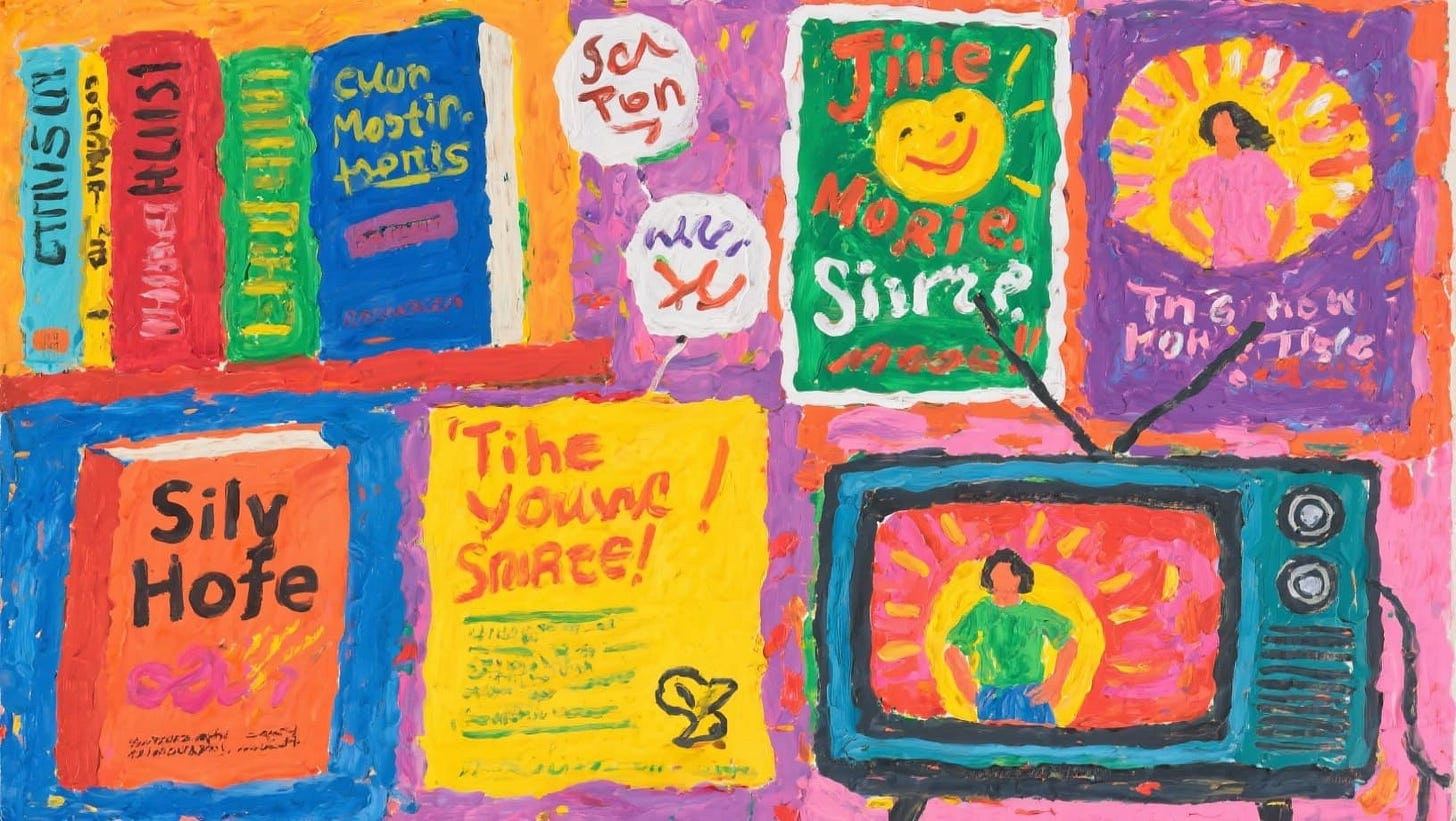

In the 1990s-2000s, media, books, and television began actively promoting the idea of “positive thinking” as a panacea for all problems. Numerous coaches, public figures, and book authors emerged, convincing people that everything in life is possible if you just think positively.

And what’s wrong with that?, you might ask. Of course, it’s wonderful for a person to maintain a level of enthusiasm and healthy optimism about life in order to lead a normal lifestyle. The beauty of positive thinking is that it provides more fuel for creating something and for movement in general. And here evolution created us this way, and our brain, which is designed for rapid information processing and understanding how to survive better, often makes decisions inertly, and therefore postponing complex issues until a crisis moment and trying to solve them on the go is a natural reaction.

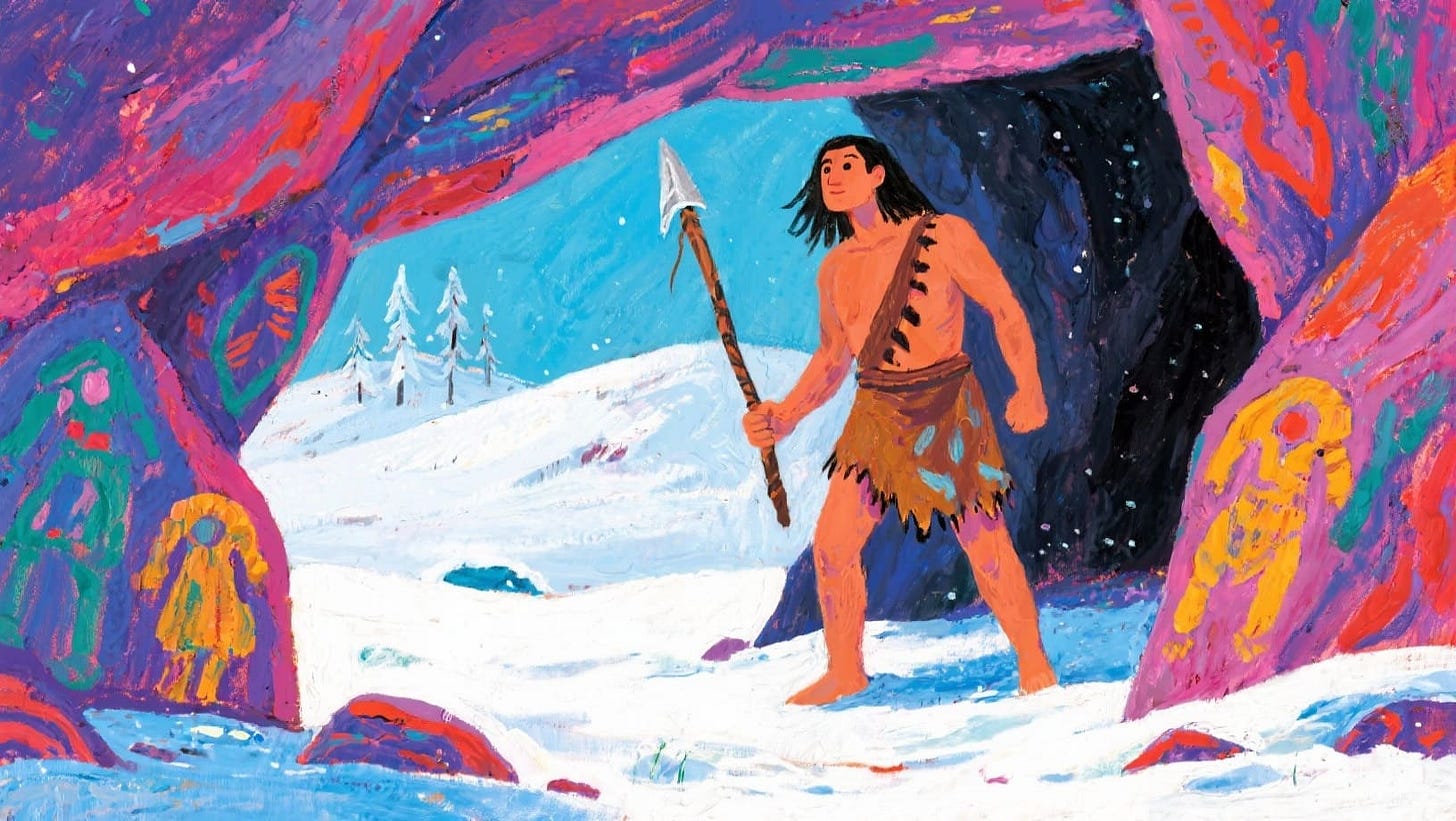

Survival first

Imagine a prehistoric human (let’s call him Karl) who has to leave his cave in the cold with a makeshift weapon to hunt an animal for his family. Karl is afraid, and for survival, it’s more advantageous to think that the hunt will be simple and quick. Otherwise, we as a species wouldn’t have taken risks, moved forward, and survived. And if someone from a neighboring cave brought bad news that there are no animals nearby to hunt, or that they’d have to go after a mammoth, which is very dangerous, most likely Karl would get angry because it would add anxiety about his future and add uncertainty about what to do next and where to get food.

But returning to the popular culture of positivity... It’s not bad in itself, like many ideas that seem good at first glance, but any good idea taken to its extreme becomes absurd, and that’s where problems begin.

What’s important to understand is that most people are not philosophers or analysts. They perceive negativity not as analysis, but as a threat to their own mental stability. Our inner Karl doesn’t want to hear or see someone who will shake our confidence and mental stability, even if we are catastrophically wrong in our ideas and plans.

Psychologically:

Negativity activates fear and helplessness. If someone talks about systemic problems, people involuntarily feel that they cannot change it. Their psyche reacts with avoidance — “you’re too negative.”

Many people live on “artificial positivity” because it’s a social norm. Especially in Western society — here it’s considered that “being satisfied” is part of good upbringing. And small talk with a colleague is unlikely to be successful if, when asked “How are you?”, you answer “Terribly, my cat died and I owe the bank a lot of money.”

Your directness is perceived as a challenge. When you notice the dark sides, you’re sort of “breaking their illusion of security.” And people don’t like that.

Therefore, for human survival as a species, most people needed to have a normal level of positive delusion. And only a minority had the capacity for analysis, reflection, philosophy, and pushing for change.

But What’s the Problem?

The problem is that you can hide problems under the rug only until they start to smell or begin to corrode the rug itself.

Nature created us in such a way that we change only when there’s a certain level of discomfort — it’s what forces us to activate all the creativity of the human brain and invent something new.

And often, to activate creativity, you need to acknowledge the problem. In addiction psychology, it’s known that the first step to treating addiction is acknowledging the problem.

The same applies to everything else.

If a person is burned out at work where they’re not respected for their skills and are poorly paid — then first they should acknowledge the obvious to themselves. Which is very difficult because it hits the ego and the realization of how much time you’ve wasted on self-soothing.

Similarly, if a person is in a toxic relationship, self-soothing won’t solve the problem long-term.

If a state has systemic problems, then of course pragmatically every government that lives for 5 years will try to divert eyes to another problem or show comparative statistics “but our neighbors have it worse.”

Galileo Dilemma

Society, raised in artificial conditions of elevated comfort, has begun to taboo and stigmatize people who think or force them to think.

And it has always been this way, unfortunately. Not so long ago, messengers had their heads cut off for bad news. Or how Galileo Galilei suffered repression from the Catholic Church for his “unpopular thoughts” about the centrality of the Sun in the planetary system.

In times when freedom of speech, until recently, in some countries had the highest indicators in all of human history — society itself became a barrier to understanding. Because understanding is often not a pleasant and positive process.

Therefore, when it comes to people like Albert Camus, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Nassim Taleb, the average citizen in everyday life will say or think: “You’re too pessimistic and negative!”

People may perceive an invitation to reflection as:

pessimism, because they’re used to it being socially acceptable to talk about positives (”how good everything is for us!”),

a threat to their self-esteem, if they identify themselves with the idea being questioned,

emotional burden — they don’t want to “carry” this volume of reality with you.

So they often say: “you’re too negative,” although it actually means “it’s hard for me to hear the truth I don’t want to see.”

So What Should We Do?

We live in a society where negativity, pessimism, thinking, reflection, and introspection are all placed in the same row and can often be scarier than death for many people.

People whom nature endowed with analytical or philosophical thinking hide in a bubble, understanding the cyclical nature of history and human nature and the possibility of a “new Inquisition” in digital format.

Fortunately, we still have, for now, Substack and a number of platforms, communities, and small islands where we can still question many issues, and where we won’t be called pessimists. Or even if we are called that — we can continue to ask questions:

“Will ignoring the meteorite really save us if we don’t look up?”

Loved this piece!! I completely agree that toxic positivity is definitely a thing, sometimes things just suck and thats ok!

I enjoyed reading this, nice work! I especially liked the rug analogy. I think it describes the situation very nicely.